The Record, 10 January 2009

Written by Robert Reid

Exhibit of late artist’s work looks at home in children’s museum, bridging generations and appealing to the child in us all.

Andy Warhol passed on to that great Factory in the sky in 1987. Nonetheless, his provocative, protean spirit dances irrepressibly throughout three of the five floors of the Children’s Museum of Waterloo Region. Those who think Warhol has no place in a museum devoted to youth should brace themselves for a shock. The Prince of Pop looks right at home. Andy Warhol’s Factory 2009 combines the conventions of an exhibition of fine art with the interactive activity of a funhouse or playground.

This is not the first time a Warhol exhibition has been mounted to appeal to children. But no previous exhibition has been so successful in imaginatively and creatively bridging the generations by appealing to children of all ages — the Eternal Child in all of us. On view through April 19, the multimedia exhibition has something for everyone — from connoisseurs of fine art, through casual gallerygoers familiar with Warhol’s reputation, to kids who would rather muck around with paint than peruse works of art. The exhibition is anchored by The Art, Inspiration and Appropriation of Andy Warhol, which showcases 60 original works by Warhol and a dozen contemporary artists who derive work directly from Warhol — the artist who turned appropriation into a cause celebre.

The juxtaposition of some of Warhol’s most iconic images — Marilyn Monroe, Liz Taylor, Jackie Kennedy, Mao Zedong, Mick Jagger and even Campbell’s soup cans — with contemporary images confirms the artist’s continuing influence and relevance. Obviously he didn’t heed his own advice with respect to enjoying a fleeting 15 minutes of fame. The gaunt, platinum-wigged poster boy for fashionable, expendable, ephemeral Art, with its trappings of mass production, conspicuous consumption and planned obsolescence, has never gone out of fashion, at least among a group of postmodern artists who draw inspiration from Warhol’s oeuvre sourced from popular culture, mass media and advertising.

At first blush, Warhol’s original screen-prints seem to get lost amid the bigger, brasher — and darker —contemporary works. That is, until you concentrate on the works themselves. Look closely and attentively and you discover, perhaps surprisingly, how well Warhol’s hold up. After 40 years, they are still fresh and vibrant, visually compelling and engaging. Looking back from the vantage point of Andy Warhol’s Factory 2009, the work — while familiar and ubiquitous — challenges the prejudices and judgments that made the rounds among hostile critics of the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s.

The artist claimed there was nothing beneath the surface of his art. What you see is what you get — or so Andy would have us believe. What he cleverly concealed, however, was what happens within the surface pigment. He fooled a lot of critics who saw nothing but surface appearances.

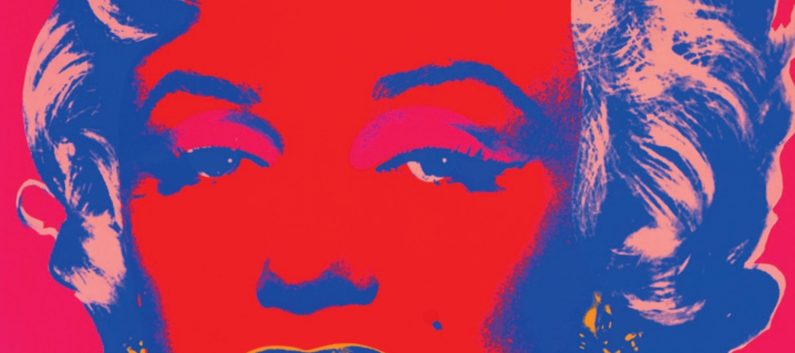

Warhol was fascinated by celebrity, but he had a profound understanding of how the cult of personality reduces fully rounded, multi-dimensional human beings to flat, garish, cardboard cut-outs. His 1967 screen print Marilyn is a case in point. The portrait bathes the legendary Hollywood actress,who starred in the movie Some Like It Hot, in a pulsating glow of hot pink and orange reminiscent of a strip joint. Although celebrated as one of the world’s sexiest women, her curvaceous body is absent. Instead, we plunge into her large, bedroom eyes, as seductive as ever. More ominously, her succulent, blue lips recall her untimely death, whether by suicide or misadventure.

Warhol was celebrated for his cool, ironic detachment — the perverse, artist-voyeur par excellence. He looked but was never touched — or so the story goes. His art was reputed to be devoid of emotion and feeling. Challenging such notions, however, is Jackie III. Mounted on the museum wall across from the portraits of Monroe, the collage of four screen print images extracted from photographs taken at the funeral of U.S. president John Kennedy transcends documentary reportage by offering an elegiac glimpse of a stoically grieving widow.

One of the exhibition’s serendipitous moments affords gallerygoers an opportunity to eavesdrop on a conversation from beyond the grave, as it were, between a president’s wife and his mistress. In both cases, the contemporary works are more overt in image and theme. Heidi Popovic’s Marilyn Contemporary Portfolio of 10 reveals the facial skeleton concealed beneath Warhol’s glamorous mask. Similarly, the piercing and burnt edging of Douglas Gordon’s Self-Portrait of You & Me (Jackies) and Self-Portrait of You & Me (Jackie) bring viewers into the conflagration that spread across America like wildfire after Kennedy’s assassination. Warhol’s background might have been in advertising, which deeply imprints his esthetic.

But he had an intuitive grasp of art history. His screen print portraits challenge the tradition of commissioned portraiture. Warhol not only transformed personal unattractiveness into public mystique, he was fascinated by classical notions of beauty. His portraits of Jackie, Marilyn and Liz provide his own take on the idealization of beauty, which he references directly in his interpretation of the Italian Renaissance artist Sandro Botticelli’s portrayal of the classical Greek goddess Venus.

The Art, Inspiration and Appropriation of Andy Warhol is only one of five distinct, though interrelated, exhibits making up Andy Warhol’s Factory 2009. Curator Marla Wasser and the creative team under the infectiously enthusiastic direction of museum chief executive David Marskell get full marks for thinking outside of the box by tying the exhibits together with an assortment of formal and thematic ribbons.

Their packaging is enough to put a smile on Warhol’s infamous blank, vacant visage. I don’t want to spoil the joy of discovery; there are numerous surprises lurking about the exhibition. Nonetheless, look carefully at Stephen Shore’s black-and-white photographs taken in and around the Factory between 1965 and 1967.

Be prepared to have the hairs on the back of your neck tingle when you see a photo of a female pointing a toy gun at the back of Warhol’s head — a chilling prophecy of what happened in 1968.

Warhol wasn’t all fun and play. Parts of his life were seedy and unseemly by conventional social standards. But let’s not confuse life with art. Andy Warhol’s Factory 2009 celebrates the art of Andy Warhol, especially the creative impulse the artist retained and nurtured from a childhood with immigrant parents in working-class Pittsburgh. There remained throughout his practice, spanning more than 30 years, a quality that all children possess in the creative heat of making art.

Most of us lose that childhood sense of wonder and awe at the common, everyday, material world around us. Warhol never did. His visual innocence is most blatant in the paintings inspired by his childhood toys (Toy Series) and the movie and comic-book heroes he revered (Myth Series). However, it also informs his multiples of Flowers, which he turns into a psychedelic dreamscape of elemental shapes and primary colour, not to mention his Campbell’s soup cans and sculpture replicating grocery store produce boxes.

When it comes to the simple pleasure and deep delight of making art, Andy Warhol’s Factory 2009 speaks to the Warhol in all of us.